How the museum might maintain its immersive Victorian display approach while simultaneously critiquing the ethos and attitudes of that era will present a difficult interpretational challenge. The museum is quoted as saying that a specific concern was that the heads were reinforcing colonial tropes of tribal savagery with visitors, and it is easy to see how this would be the case considering the organisation, display furniture and minimalist interpretation in the museum. Such proactive engagement with a decolonisation process is to be warmly welcomed but raises interesting questions for the Pitt Rivers’ unique display identity. The Pitt Rivers decision takes place as part of a wider review of collections, displays and interpretation which has seen other human remains removed from display until better dialogue can be had with relevant communities in South America. The Pitt Rivers collection contains both human and animal head tsantsas.

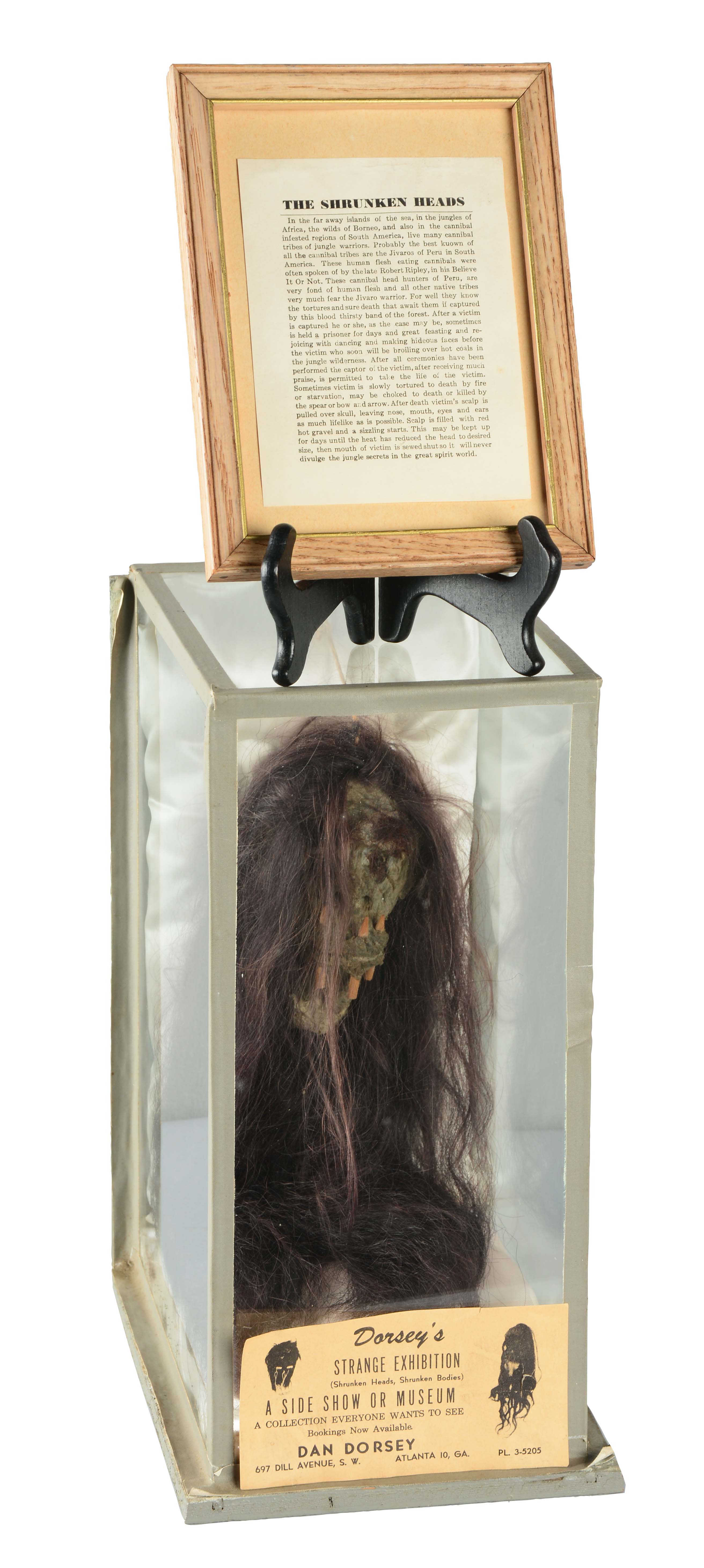

The increasing interest in these heads in the west and the prices paid for them, however, led to an increase in inter-tribal violence and the production of numerous ‘fake’ tsantsas using monkey or sloth heads. They were therefore powerful ritual objects with a role to play in the strength and fertility of the community and its lands. Traditionally the preserved heads of enemies killed in battle, tsantsas were not simply war trophies but thought to contain (and control the retributory power of) the soul of the individual. Prior to its re-opening after the Covid-19 pandemic, the museum has recently announced that it has removed one its most popular exhibits from display – a number of Ecuadorian and Peruvian ‘tsantsas’, better known as ‘shrunken heads’. Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum, famous for its Victorian-style displays of ethnographic material from cultures across the world, has become a leading institution in openly discussing the need for the decolonisation of museums.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)